Wittgenstein stated that every philosophical problem is founded on the phrase, “I don’t know my way about.” Consequently, philosophical activity is engaged in the unravelling of perceptual and epistemological conundrums, but I don’t want to occupy myself with such conundrums today.

Instead, I’d like to apply that same phrase - “I don’t know my way about” - to learning.

All learning should begin with the humility and awareness to acknowledge an initial ineptitude (e.g. an inability to do something or see something or know something) along with the willingness for one to find his or her way about in some shape or form.

In other words, an individual may start out “blind” to certain “aspects” or “(meaningful) patterns” in a certain phenomenon but the individual comes to “notice these aspects or patterns” through carefully arranged activities and repeated practice … often guided by others who are more skilled, perceptive, and experienced in the phenomenon.

In this case, “aspects” refers to “salient features” in some phenomenon, such as the features of language, or of an alphabet or even the rules of engagement in particular social situations. In the case of each phenomenon, an individual must learn to recognise and decipher these patterns. At the beginning, the learner may stumble along, but - through guided practice and experience - the learner navigates the phenomenon with increasing fluency and thoughtfulness.

“Understanding comes in degrees.”

Perhaps the following quote from Philosophical Grammar can go further to illustrate how our learning can lead us to read the world in ways which come to be increasingly more meaningful through practice.

"Does it make sense to point to a clump of trees and ask ‘do you understand what this clump of trees says?’ In normal circumstances, no; but couldn’t one express a sense by an arrangement of trees? Couldn’t it be a code?”

Couldn’t such a clump of trees reveal something about the local ecology to one who is trained to discern patterns in a particular way? The answer is clearly “yes”. There is nothing outlandish in Wittgenstein’s proposition.

Whilst the above example does shed some light on aspect seeing, it also allows me to make another point about learning. Let’s imagine that two individuals pass by the same forest on a regular basis. Even though both individuals may experience the forest regularly, it may be the case that only one of the two individuals has been initiated into the ways of seeing such that he or she notices something particularly meaningful in “a particular clump of trees.” In other words, one person has been initiated into a certain form of aspect seeing, whilst the other individual hasn’t, even though they may both have some experience with the same phenomenon.

This has particular applications to literacy. As an obvious one, you may have two learners who both have experienced print but one of the two learners may have benefitted from better instruction in exploring the intricacies of the alphabetic principle than the other. Similarly, we may have two learners who have both experienced ample amounts of shared book reading, but only one of two learners has engaged in the types of sustained conversations around characters, setting, sequencing, and artistry that will benefit him or her later on (e.g. in school-based conversations).

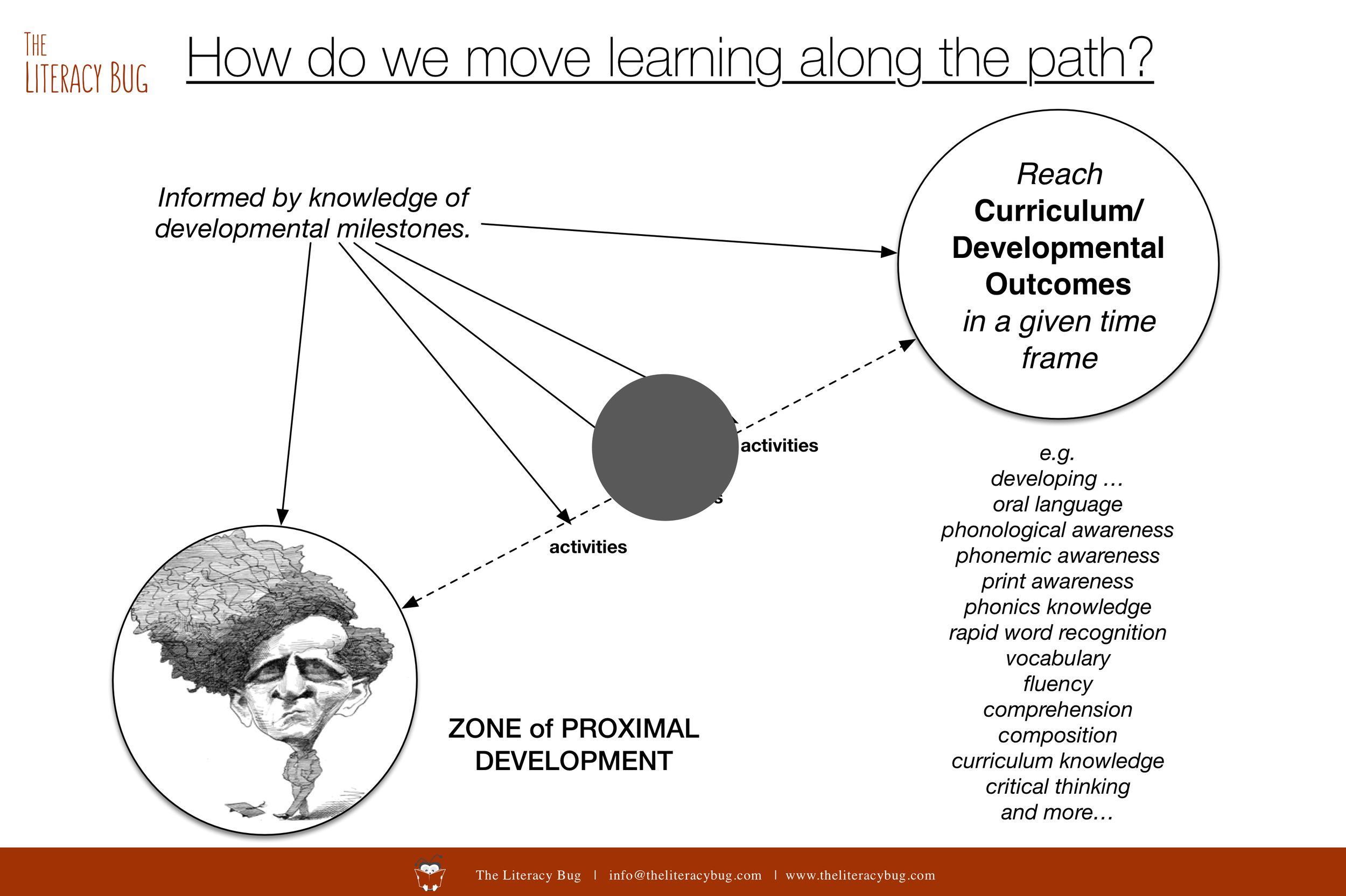

Ultimately, the learner is a novice and the teacher is the expert who attempts to draw the learner’s attention to significant elements in order to manipulate them and interact with a phenomenon with dexterity. We - as teachers - are initiating learners into ways of “finding one’s way about.” As a result, the teacher’s role is to make “unsurveyable wholes” surveyable, if I use the words of Hans Sluga (see definitions at the end of this blog entry).

I must acknowledge that there are intrapersonal, interpersonal and context factors that have a bearing how and what an individual learns. In other words, individuals will differ in their cognitive abilities, in the learning relationships that have they have formed and in the environments in which they live. All of this will impact what/how one processes.

With that in mind, I’d like to end (or near the end) with another example raised by Wittgenstein. He asks us to imagine an alien learning the game of chess. In this example, he want us to ask ourselves, “can this alien intuit the rules and purpose of chess merely by observing the game being played? No explanations. No demonstration.” The answer would be “no”. If possibly “yes”, it would a painful, lengthy and error-ridden process of trial and error which could be alleviated by at least some stages of instruction and explanation, though, even this would be impacted by the lack of a common language between the alien and the chess players. Beyond the rules, the alien would also need to be brought into the whole purpose/context of the playing of chess and the playing of games in general, for that matter. Consequently, the whole process of initiating one into ways of seeing and doing is a lengthy process which grows over time through both skill acquisition and conception development.

That’s it for today, and I know that this is the first update to The Literacy Bug in quite some time, and it’s good to be back. I’ll leave you with a number of terms and definitions below that explore elements of “aspect seeing” and “finding one’s way about”. Thanks for your time. I’d be interested to know your thought. How would you apply the ideas above? What relevance (if any) do they have for you? In the meantime, please explore and enjoy!

RELEVANT TERMS & DEFINITIONS

ASPECT SEEING - (also known as noticing/seeing aspects) To see and interpret aspects (or phenomena) as meaningful, or as imbued with meaning. To discern aspects (or patterns) in a whole and to organise how these aspects fit into a system.

ASPECT BLINDNESS - Refers to the inability to discern or detect aspects. Arises as a result of two possible circumstances. First, an individual does not see (or notice) aspects as meaningful or does not turns one's attention to certain aspects in one's environment. The person has not been brought into discerning and interpreting the aspects in a particular way.

NOTICING ASPECTS - To notice salient features when one is making observations. This requires more than merely seeing. This requires the ability to distinguish features and to see features as significant. For instance, an air traffic controller comes to be able to assess and interpret the instruments before him or her.

SEEING AN ASPECT - Wittgenstein refers to two ways of seeing. The first being "I see x", which refers to the physical act of seeing something. The second being "I see x as (meaning) something". For instance, the written script may appear as either assorted lines on a page or meaningful language with significance. In addition, one may notice a tree in a particular position next to a house. An individual may also see it as fitting into a series of consequences, and so imagine it as possibly falling onto the house. A further example would relate to an artwork's ability to conjure associations with - let's say - peace or freedom. The viewer would need to be able to notice one or more salient features that would move one to interpret or react in a particular way.

SEEING CONNECTIONS - Wittgenstein emphasises that a thinker must piece together elements of experience or of knowledge so as to gain a command of how a system works. In Philosophical Grammar, Wittgenstein writes, "A puzzle picture. What does it amount to to say that after the solution the picture means something to us, whereas it meant nothing before?" And Ray Monk (2005) observes, “An Ubersicht produces the ‘understanding which consists in “seeing connections’” (p 66). In this case, building knowledge and engaging in practices requires an individual to see how the knowledge fits together and how a practice is connected with a form of living.

UNSURVEYABLE WHOLES - It is Hans Sluga (2011) - not Wittgenstein - who uses this term, though it is consistent with Wittgenstein's philosophy. Sluga emphasises that phenomena - such as language, the environment, history - are by nature complicated, immense and unsurveyable. Humankind, nevertheless, develops systems of analysis, fields of knowledge, and ways of seeing that act as tools to make sense and to "survey" or organise what would otherwise be unsurveyable. William Gaddis provides an illustration of this in his novel JR. A history teacher stops a Year 7 lesson to inform his class that history is a lot more complex than the neat historical narratives seem to indicate. He stresses that generations of historians work to preserve order in history so that events do not eventuate as tangled and insignificant.

SURVEYABLE REPRESENTATIONS - A surveyable representation involves an attempt to develop a way of looking at a set of phenomena that allows an individual and /or community to make sense of and - in many cases - to manipulate particular phenomena. Similarly, a system (of culture, of language, of life) may be substantially complex, which would require one to develop a method of analysis, a way of thinking, or a manner of living that would make the 'unsuveyable whole' increasingly 'surveyable'. Consider - for instance - the principles of a religion, or the rules of grammar, or a Marxist explanation of socio-political relationships. Each are ways of representing phenomena. It is important to remember that the representation is a way of perceiving the phenomena, rather than being the only possible description (or rendering) of the phenomena.

WAYS OF SEEING - Wittgenstein uses two metaphorical examples to illustrates how perceptions are subject to the way that an individual arranges experiences into meaningful patterns. The most famous metaphor applies to the rabbit-duck image. From one perspective, the drawing appears as a duck. From another perspective it is rabbit. Regardless of the interpretation, the actual image does not change. The only thing that changes is how one comes to see it. The second metaphor applies to the image of a cube. One arrangement presents the cube as jutting out of the page and at the reader. The other sees the cube recede into the depths of the page. To be able to see both images, one needs to shift one's gaze and reconceptualise that which is under investigation. However, one who is aspect blind may be unaware or resistant to any alternative manner of arranging and interpreting the facts of the case. One who continuously sees in a certain manner may be unaware of other possibilities. One must - then - ask, “how does one come into a certain way of seeing?”

STAGE SETTING - Stage setting refers to all the preliminary activities that prepare one to make meaning or to establish a practice. For instance, Wittgenstein is quick to remind his audience that a substantial amount of preliminary experiences must be in place for one to acquire language, or make sense of algebra, or to become a mechanic. We must ask ourselves, "what are the prerequisite experiences, expectations, role models and understandings that will lay down the tracks on which the learning will occur?" And "do we have the resources, models and opportunities to carry on with the learning so it becomes practiced and relevant and useful?"

SCAFFOLDING - We come to learn methods of activity and systems of knowledge. These methods and systems become reinforced as they are shaped through our interactions with the notion of learning presented to us in a circle of influence. Deep grooves are set in our thinking and our behaviour. In this sense, education proceeded first as a form of training in ways of doing and seeing, which become prototypes for our thinking and decision in future events. Our methods, our experiences, our expectations, our schemas are initially scaffolded for us in the learning process. In turn, these habits, beliefs, rituals and methods become the scaffolding for our engagement with the world in the future. When one is brought into knowledge, one should be brought into content and method at the same time.

COGNITIVE APPRENTICESHIP - A cognitive apprenticeship brings people into different ways of thinking, problem solving and processing. Cognitive apprenticeship is a model of instruction that works to make thinking visible. The practices of problem solving, reading comprehension, and writing are not at all obvious- they are not necessarily observable to the student. In apprenticeship, the processes of the activities are made visible as the processes of thinking are modelled, jointly constructed and guided.

BOOTSTRAPPING - Bootstrapping occurs when an individual becomes aware of the patterns and rules governing a phenomenon, such as in language or in a practice. The learner develops an appreciation of and a template for meaningful/permittable combinations or actions. By becoming aware of allowable patterns, one can direct one's attention more efficiently since one is better able to anticipate what to expect or how to act. For instance, the first encounter of a new social situation may give one trepidation. However, regular practice allows one to accumulate the experience to be more confident in what to expect and how to act (to play the game). On the other hand, the experience may also limit creativity since one may develop a familiarity that limits (bootstraps) one's ability to imagine other possible ways of seeing or acting. In relation to language, experience teaches one the patterns of spelling, grammar, and discourse. Therefore, one becomes more efficient at predicting or discriminating correct form and use.

CONTINUOUSLY SEEING AS - Refers to the penultimate stage of the learning process (if we take critical reflection as the final stage). At this stage, one does not struggle to notice aspects or to interpret observations. At this stage, the individual has acquired a way of seeing or of interpreting that becomes automatic. To "continually see as" is to commit to or to acquire a certain way of seeing, whether we are referring to perceiving language, to moral practices, to aesthetic judgement or to spiritual beliefs. In all such cases, a certain way of seeing has been incorporated into one's world picture.

STRUCTURING STRUCTURES WHICH STRUCTURE STRUCTURE - Refers to those aspects within one's environment that gives shape to practices, influences what practices one is part of, and comes to sustain practices. The concept is closely related to Bourdieu's concept of habitus, and it refers to the background to practices and knowledge which is often taken for granted or assumed. For instance, an actor must be aware that the ability to attain a career in acting is built on the premise that a culture values the concept of acting and drama, and the culture can allow/afford for members of its community to embody the role of actors. It can be the case that one feels entitled to a form of living without admitting that this form of life is reliant on certain capital, practices, methods of production and division of labour to be in place for the practice to be sustained.

HABITUS - This is a concept used by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who cites Wittgenstein as a key contributor to his thinking. Habitus refers to the lived conditions (or context) that serve as the foundation for certain practices, knowledge, tastes and values. It most closely aligns with Wittgenstein's use of the "form of life" concept. Bourdieu would argue that whilst habitus is key to understanding a practice or a way of thinking, it is often poorly analysed or entirely ignored when people consider social, cultural or learning event.

CULTURE - Stanley Cavell claimed that Wittgenstein was a philosopher of culture. That is, Cacell asserts that Wittgenstein claims that our knowledge, our practices and our values are derived from the interactions of a community. There is considerable evidence to suggest that this is the case. In the Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein stipulates that meaning is derived from the form of life to which our language and practices occur. In addition, On Certainty emphasises how one's knowledge and world pictures are arrived at through one's "upbringing"