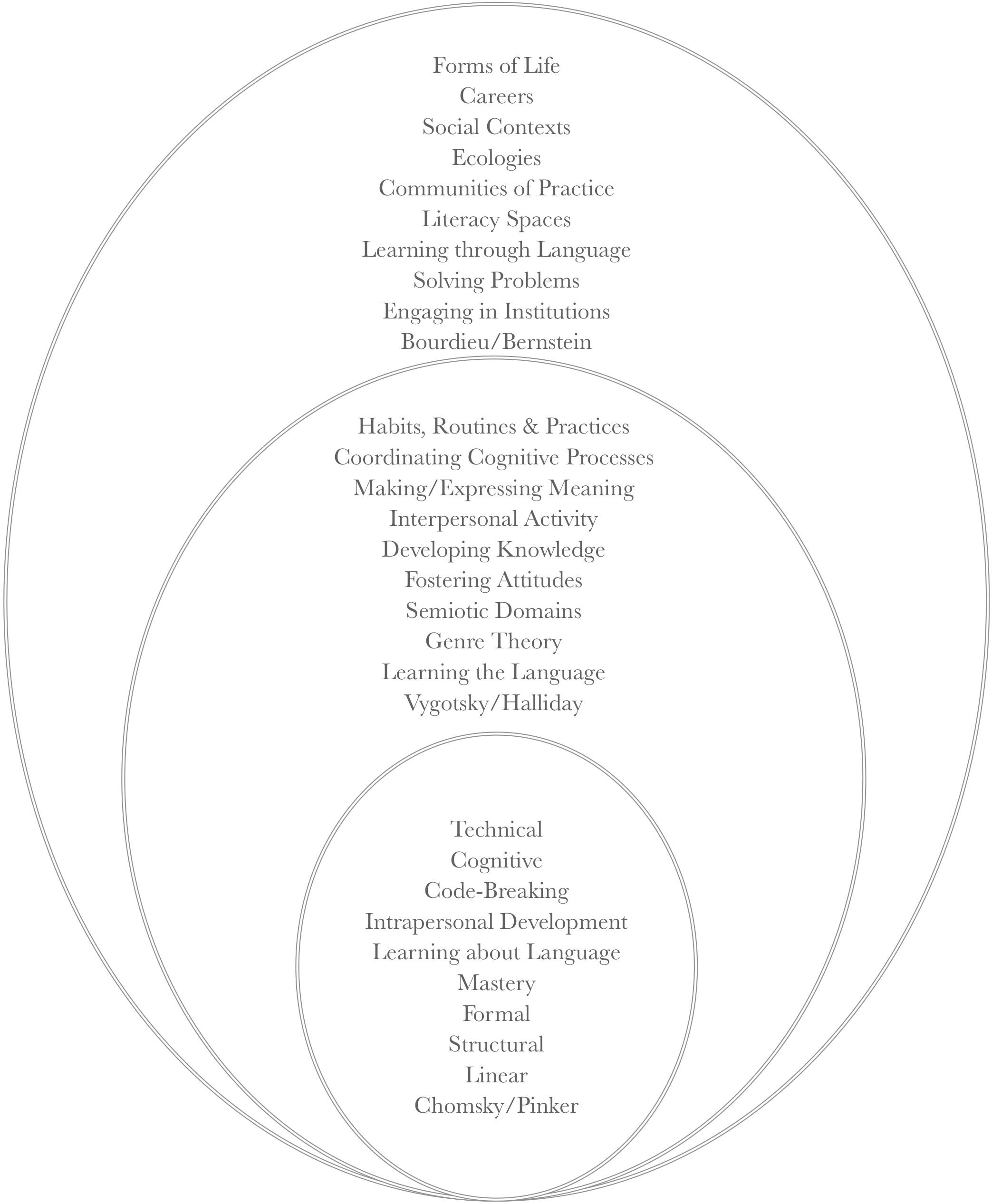

Previously, we have alluded to the changing direction of this website; it will focus more space on the many dimension of literacy and less space on the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. In an effort to outline the dimensions of factors contributing to comprehensive literacy development, we would include:

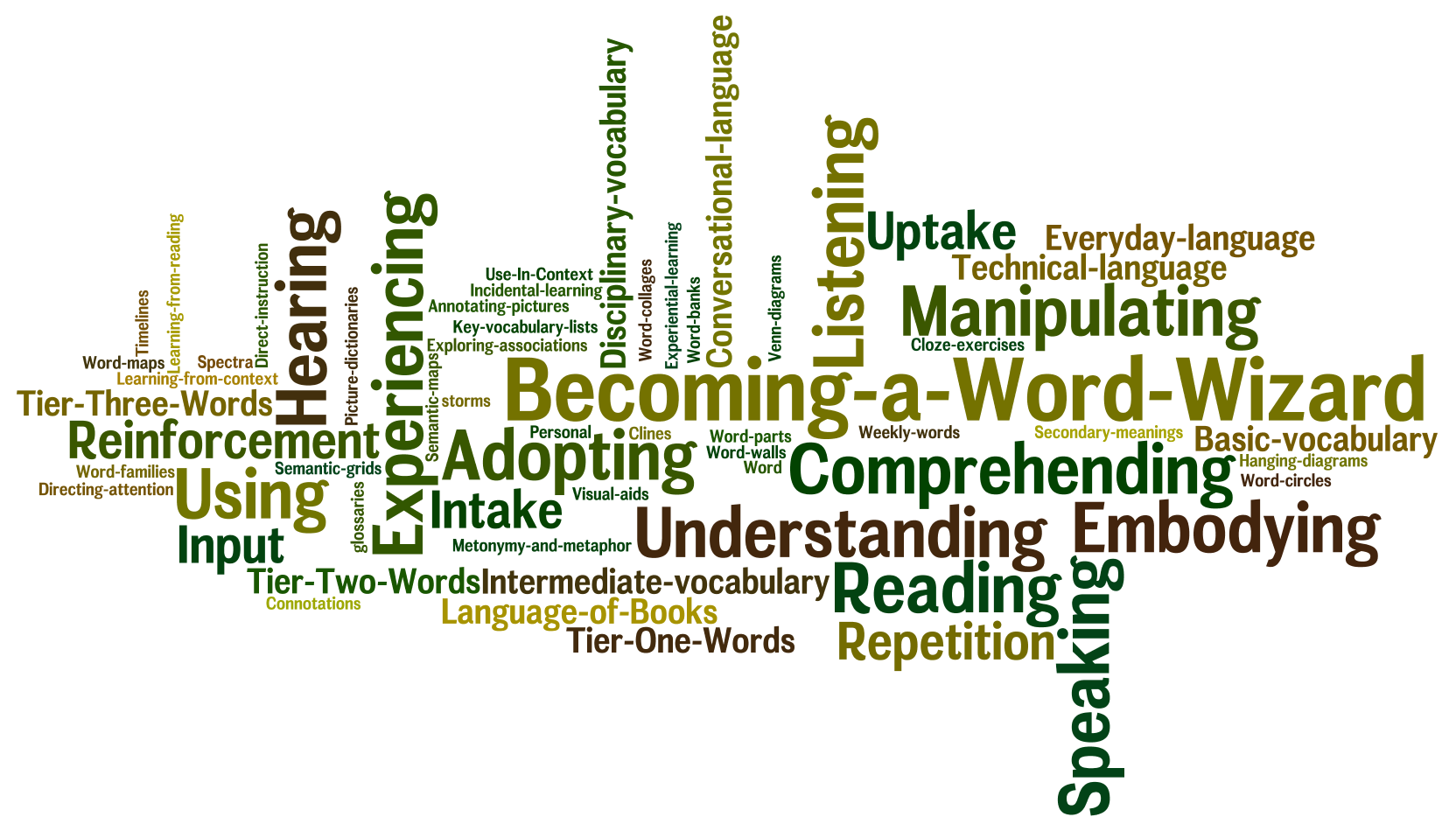

- Robust development of oral language in language-rich and literacy-rich environments;

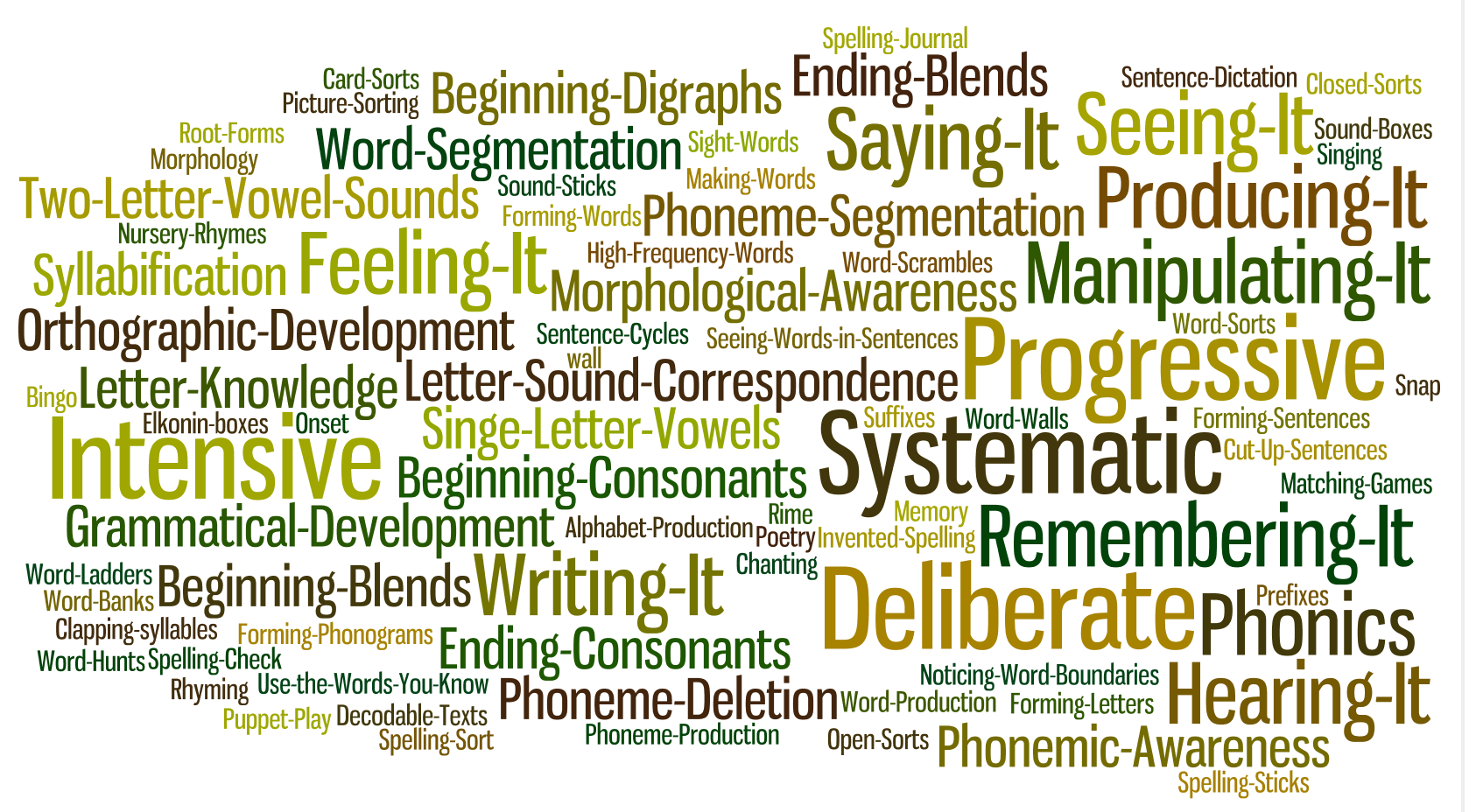

- Clear, systematic and intensive development of phonemic awareness (when suitable);

- Further systematic and progressive development of alphabetic skills, including phonics, spelling and morphology;

- Wide ranging support of vocabulary development from a very young age;

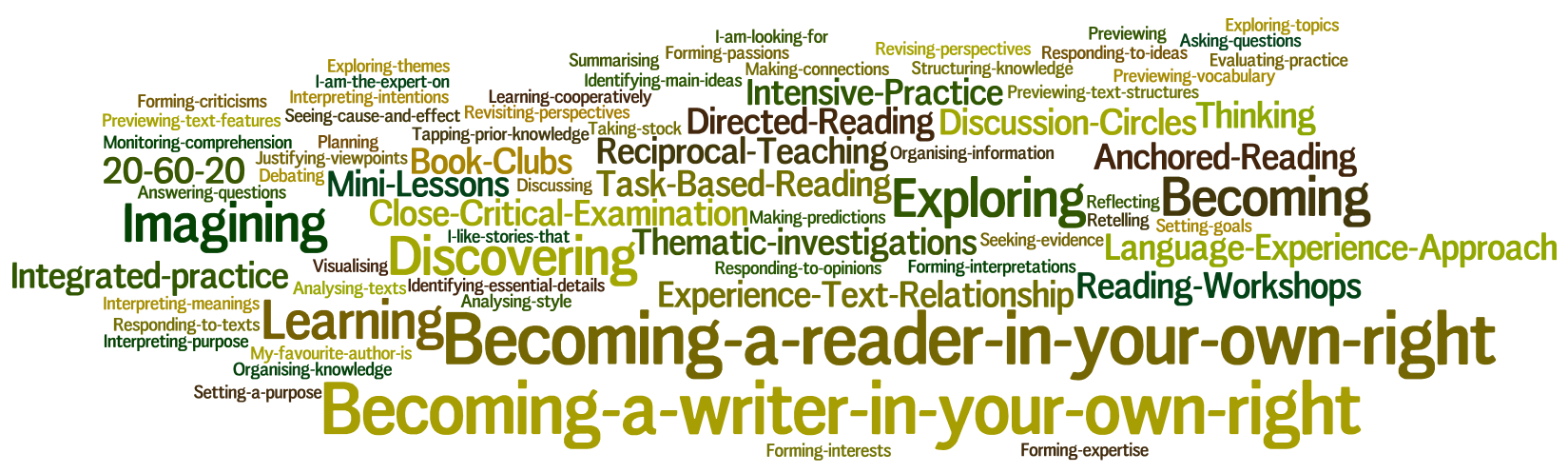

- Expert utilisation of read-alouds;

- Skilled orchestration of language experiences;

- Substantial time set aside for fluency practice (include time for independent reading);

- Attention to ultimate goal of reading instruction: comprehension; and

- Apprenticeship into the craft of composition; and

- Ongoing and deepening construction of knowledge (the real goal of learning).

The above areas are not mutually exclusive. Ultimately, they should also be unified by thematic investigation(s).

In this pursuit, we want learners to develop:

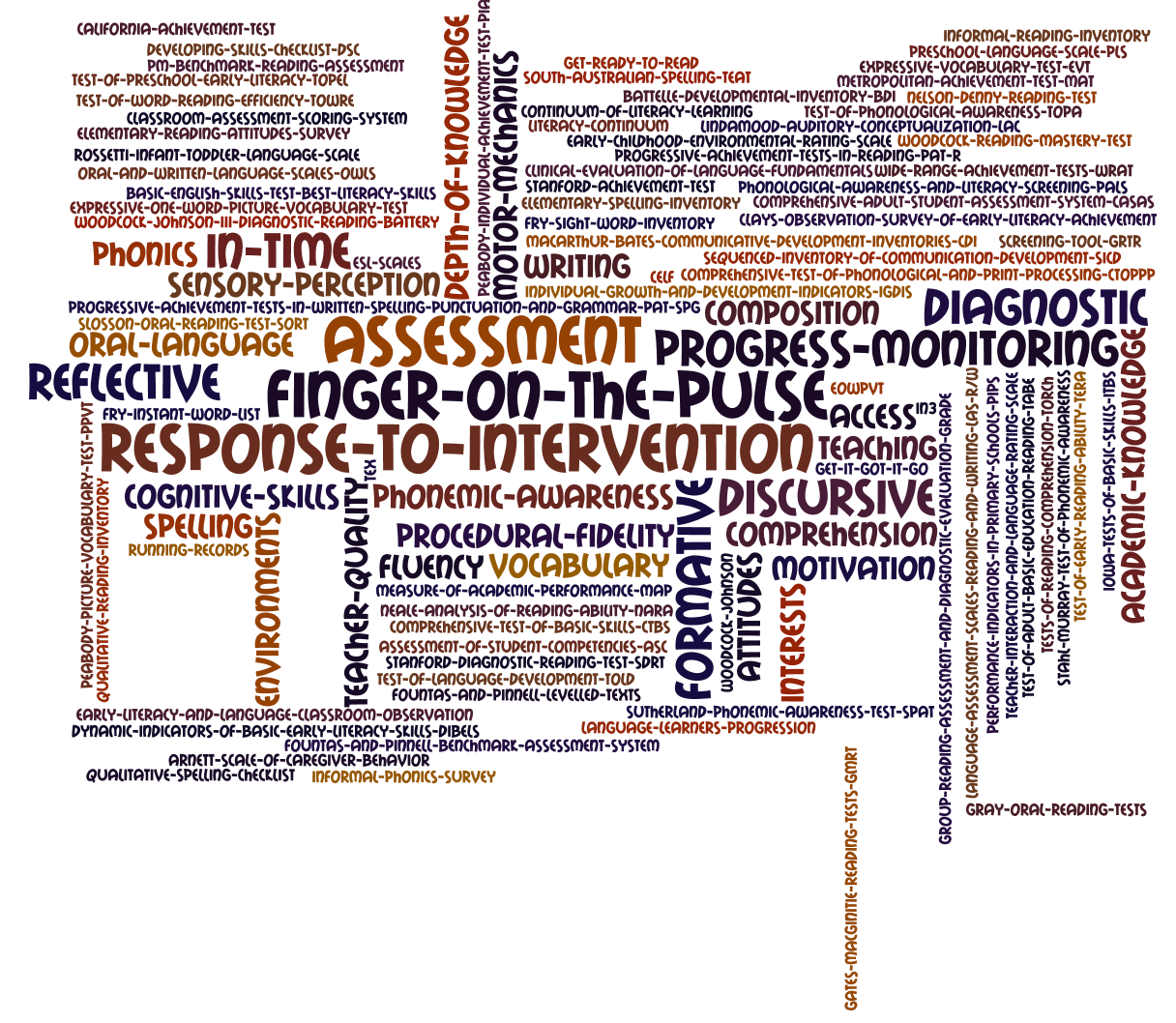

- Cognitive skills (e.g. pattern recognition, memory retrieval) and meta-cognitive awareness;

- Motivation, attitudes, interests and expertise;

- Non-verbal skills and talents; and

- Careers and identities.

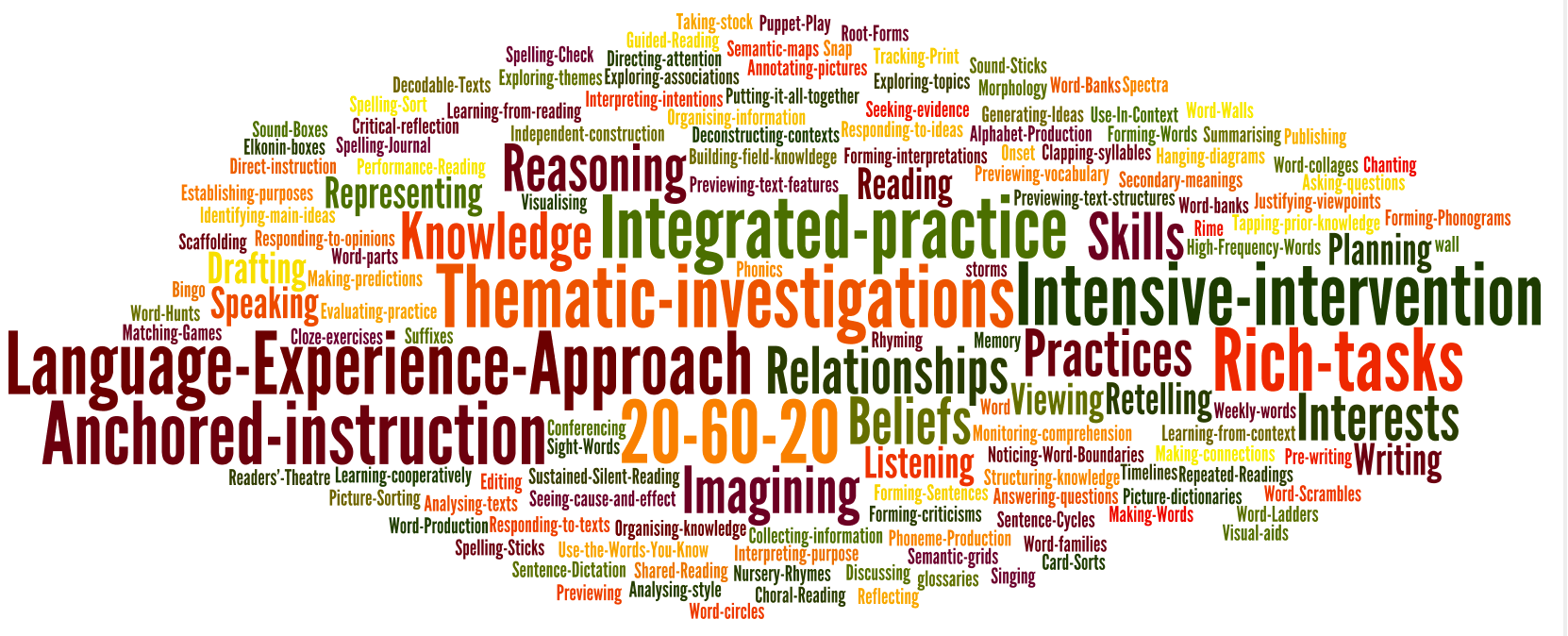

Therefore, the developing website will come to include specific advice in such areas as:

- Fostering Oral Language;

- Developing Phonemic Awareness;

- Solidifying Alphabetic Knowledge;

- Extending Vocabulary;

- Utilising Read-Alouds;

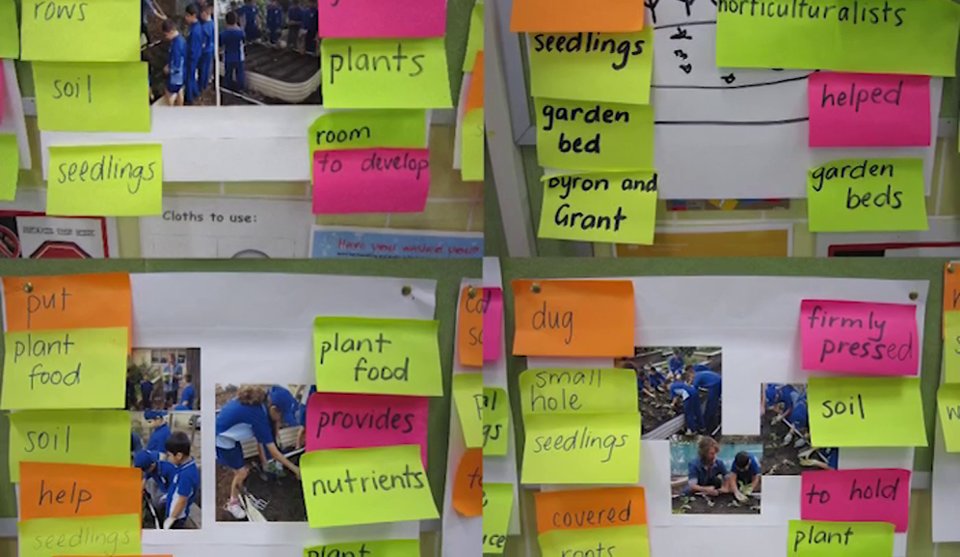

- Orchestrating Language Experiences;

- Shaping Fluency;

- Ensuring Comprehension;

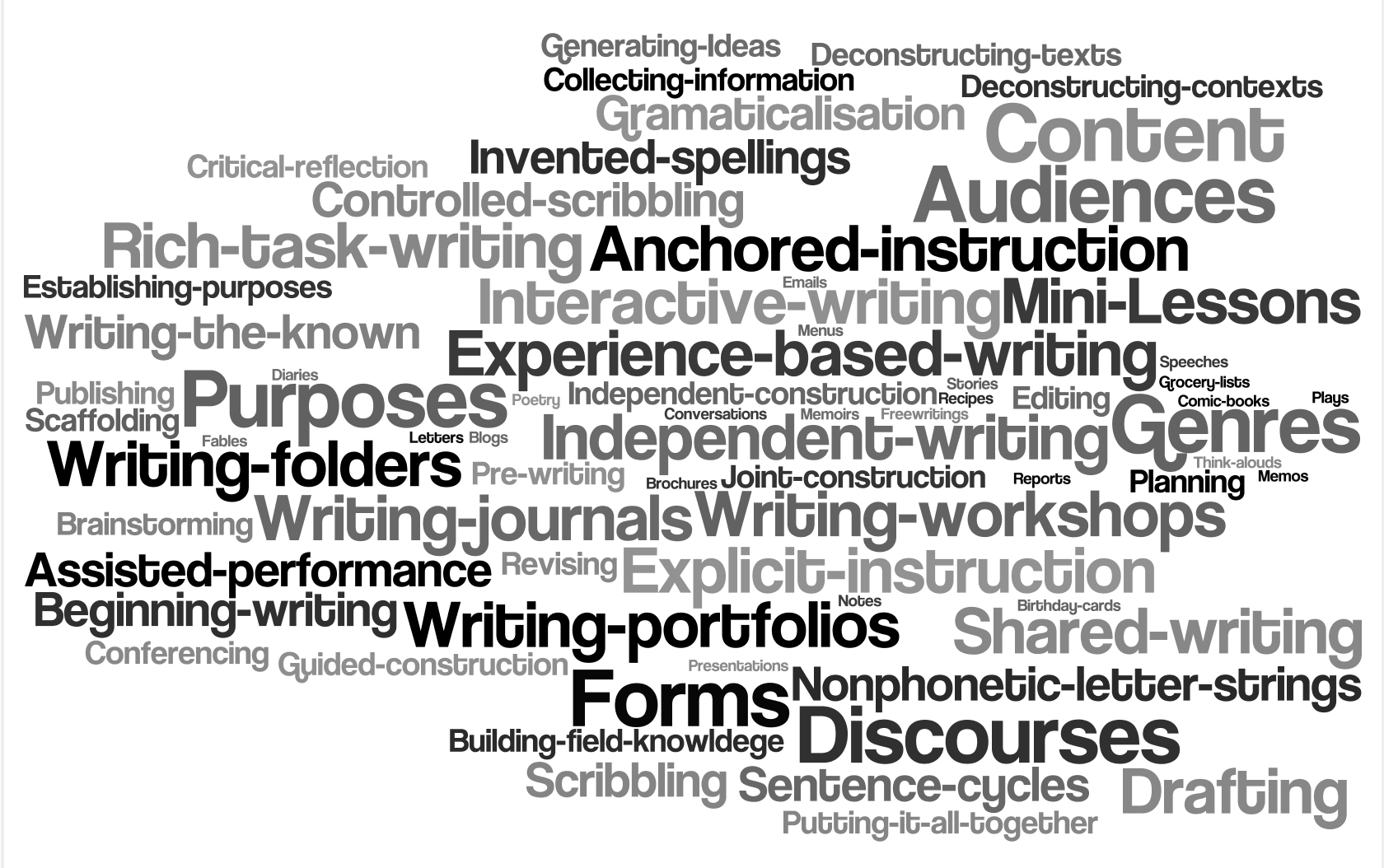

- Facilitating Composition;

- Integrating Content Learning;

- Building and Representing Knowledge;

- Scaffolding Action;

- Fostering Interests and Expertise;

- Pulling All of This Together Into Integrated Teaching and Learning.