Welcome to Wittgenstein On Learning

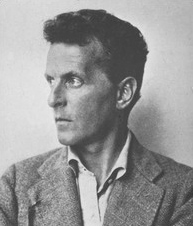

Wittgenstein On Learning provides a Wittgensteinian view of language, literacy, numeracy, literature, thinking & more. It goes without saying that the site is inspired by Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 - 1951), who is considered by many to be one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century [1] [2] [3], and is known for his contributions to the philosophies of logic, language, mathematics, culture & the mind. This website is not a summary or an evaluation of his philosophy, though. Instead, it takes the philosophy as a launchpad to reflect upon contemporary aspects of education, whether it is about language & literacy acquisition or equity & culture or knowledge & doubt. For initial summaries of what makes our approach "Wittgensteinian", please explore the the Introduction, the Why Wittgenstein?, the Key Principles and the Two Wittgenstein pages.

In the meantime, a Wittgensteinian view of language, literacy and learning recognises that people are transformed through learning (and by what is learnt). When we learn a language, and when we develop a literacy, and when we work with numbers, we acquire tools in the community and a capacity to participate (to fulfil a form life in the stream of living).

“Every child, scrawling his first letters on his slate and attempting to read for the first time, in so doing, enters an artificial and most complicated world.” (Hermann Hesse, Quoted by Wolf, 2008, p 79)

If one falls behind (or starts behind), if one speaks a language that isn't recognised, or if one is meant to just know how to act and perform in worlds (contexts) only recently encountered without space, time or a guide, then we should be alarmed by, or at least sympathetic to, the challenges being set for the learner. We need reminders to direct our attention to the complexities of language, literacy, learning and culture.

The work of the philosopher consists in assembling reminders for a particular purpose. (PI, 127)

If there is any core purpose to Wittgenstein's reminders, it is this: to remind us that we didn't always "see" and "speak" and "read" and "think" and "act" and "believe" and "imagine" in the ways we do. We must be reminded that we came into our language, our learning, our habits, our knowledge and our values over time and over repeated experiences often reinforced by certain material conditions and "teaching" - some scaffolded and monitored and others more tacitly and immersive.

It is often easy to take the conditions for our learning for granted, since these conditions may lie deep in our culture, our context, our relationship and our past. These conditions are inextricably linked to the material, social and economic conditions in our lives. As teachers, we must rigorously ask, "what are we asking students to learn? Do we have all the elements in places to create optimal spaces and opportunities for this learning to occur? And is this learning - that which I am asking the students to engage in and acquire - of particular relevance to the time and space in which we are living at this very moment?"

We shouldn't forget that Wittgenstein was a primary school teacher between the writing of the Tractus Logico-Philosophicus and the Philosophical Investigations. Whilst it is safe to say - from multiple sources - that he was not an outstanding - or even good - teacher, I believe that the dilemmas he encountered as a teacher in rural Austria informed his philosophy.

In rural Austria, he observed the rural children from farming backgrounds struggle with a curriculum that privileged urban knowledge. He saw how knowledge was context-dependent and how knowledge arises and makes sense within a form of life.

Aims of Wittgenstein On Learning

- To use Wittgenstein's concept of aspect seeing as a platform to explain how one's perceptual skills (e.g. literacy), knowledge (e.g. historical appreciation), practices (e.g. mechanical skills) and beliefs (e.g. democratic ideals) develop over time in stages through repeated practice, enabling opportunities and guidance from others in a cultural setting;

- To ask us all to be mindful and respectful of the experiences, rituals, practices, cultural artefacts and "learning moments" that give shape to the ways we live, see, act, react and believe by showing how all learning and language has its form, content, purpose, context and history, all of which may not necessarily be apparent to the acculturated learner or the outsider; and

- To understand what it means to ensure equity in the opportunity for all to learn whilst respecting the cultural, social and economic pluralism exhibited within and across local, national and historical boundaries.

In short, nothing a priori. There are no universals. All is learned. That which is learned becomes the foundation for later learning. Any cultural similarities in learning practices are due to similarities in human needs that are present across time and space. Our learning comes to serve as the framework to our perceiving, interpreting and acting, which evolve, alter direction, fragment, decay, leap, etc. Therefore, the trajectory for learning is neither determined nor automatic. At the same time, the trajectory of learning is not arbitrary. The trajectory is conditioned through context, practice and the will, and this conditioning is far from simple and rarely pure. If we refer to Stanley Cavell’s terminology, we can see the human form of life as existing across two planes: “a vertical (or biological) [plane] – whereby the human form of life is distinguished from other forms of life (higher and lower); and a horizontal (or ethnological) [plane], which accounts for socio-cultural differences within a form of life.”

In teaching you philosophy I’m like a guide showing you how to find your way round [a city] ... from north to south, from east to west ... [Only] after I have taken you on many journeys through the city, in all sorts of directions, ... will [you] be able to find your way about. (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations)