For quality education to become a reality, there must be coherent & developmental instruction; passionate & visionary teachers, peers and/or caregivers; quality materials, resources & practices; and a respect for the learners' cultures, experiences and pathways. The learner must be "a biologically and socially adept human being ... susceptible to training ... [with] fundamental trust [in] the authority of the teacher ... [engaged in] socio-linguistic interaction ... transmissible ... through enculturation" (Moyal-Sharrock, 2010, pg 6 - 7). We must work to create joint attention in which all participants share a sense of mutual accomplishment within enabling structures.

As mentioned previously, equity in opportunity to learn requires that the learner has:

- Substantial amount of engaged time on task which is not disrupted by teacher and student absenteeism;

- Access to quality teaching, resources and environments;

- A coalition of support including teachers, parents, community members and peers;

- Safe and secure environments free from discrimination and abundant in high educational expectations;

- Respect for the funds of knowledge that the learners bring to the learning environments and their cultural way of knowing. This includes a respect for the cultural, social and economic space and the way of knowing particular to it and its occupants, even in an era of globalisation, nationalism and standardisation;

- Structuring structures that structure structure, which refers to the aggregate effect of supportive environments, financial capital, social relationships and the employment/educational marketplace;

- Resilience, grit, agency and purpose demonstrated by learners as well as from their teachers and their caregivers; and

- Substantial opportunities to practice with key opportunities to turn such practice into sustained existence (e.g. jobs, clubs, etc).

However, we must also engage with the antithesis of this ideal. If we supposedly know the essentials for achieving equity in opportunity to learn, why is it that we allow the achievement gap to widen? Do we put this down to lingustic differences, cultural differences, discrimination, inadequate or negligent teaching, or disagreement over the rationales for schooling? (Au, 1998) Are “disadvantaged” learners in environments that encourages complacency, a lack of self-efficacy or a lack of rigour? Are there inadequate learning materials, limited learning opportunities, and ineffective feedback? Are learners in a world full of risks, harms and threats? Do we know the assets that students bring to the learning and are we prepared to provide the opportunities for transformative education?

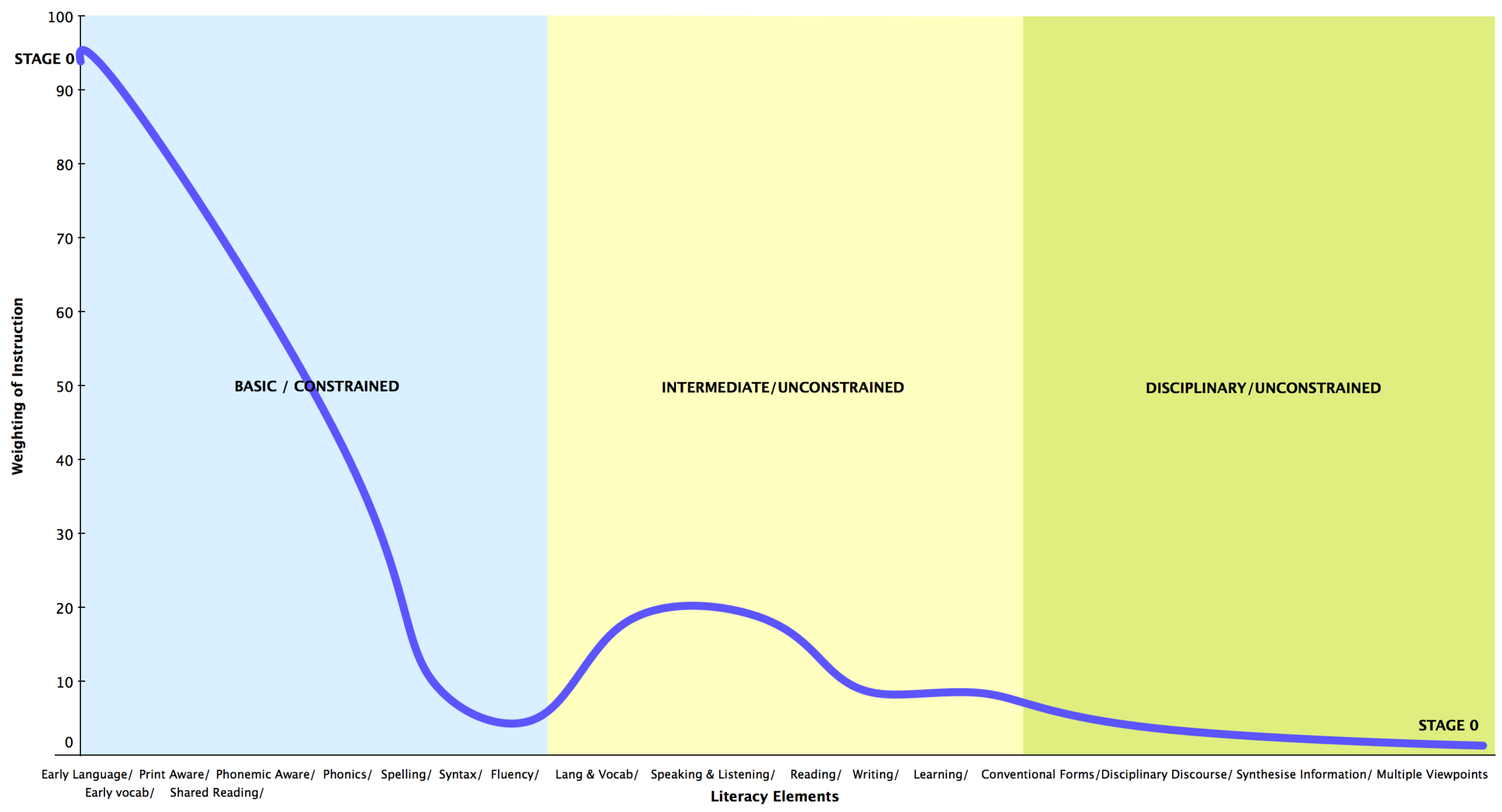

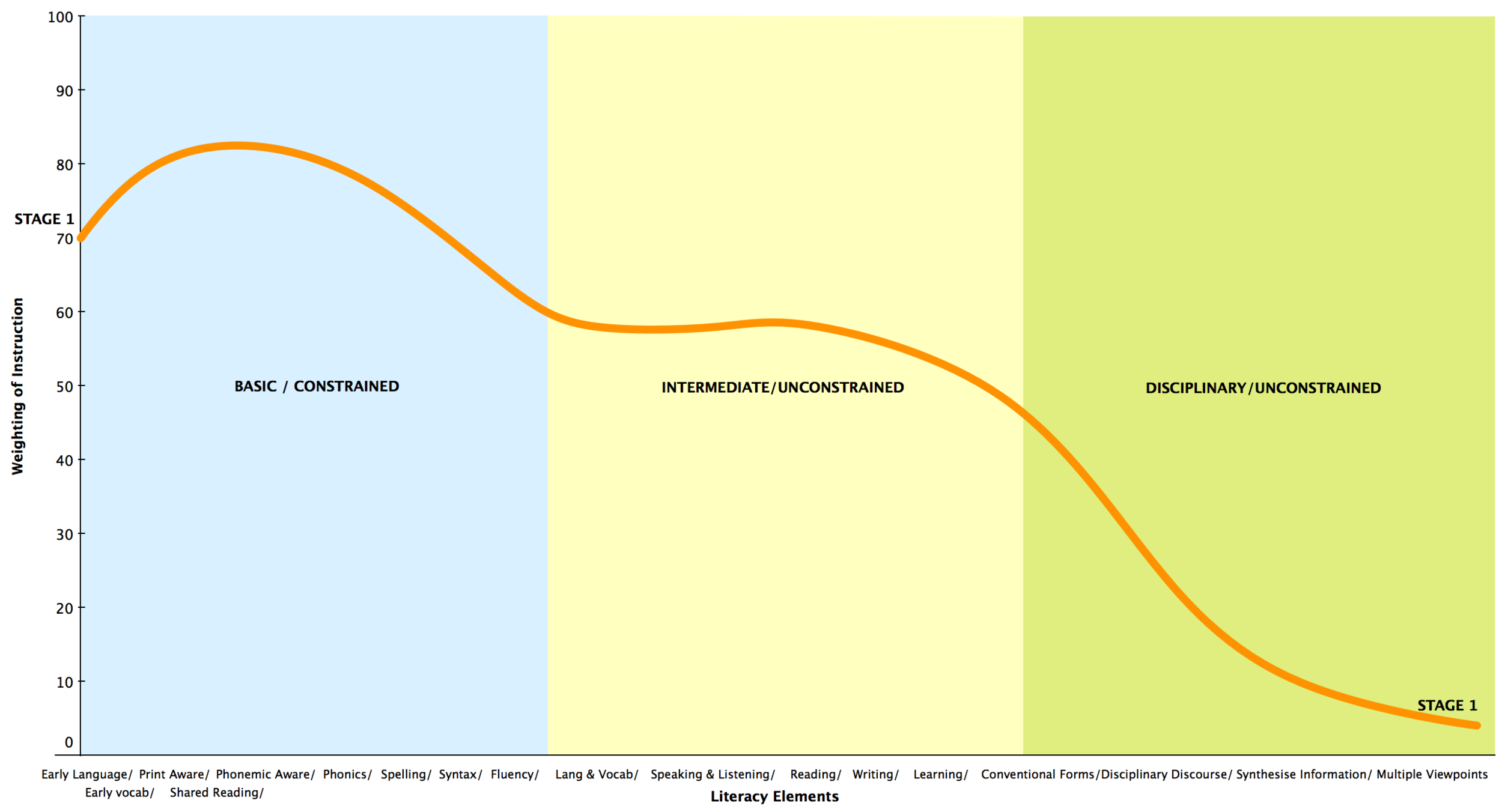

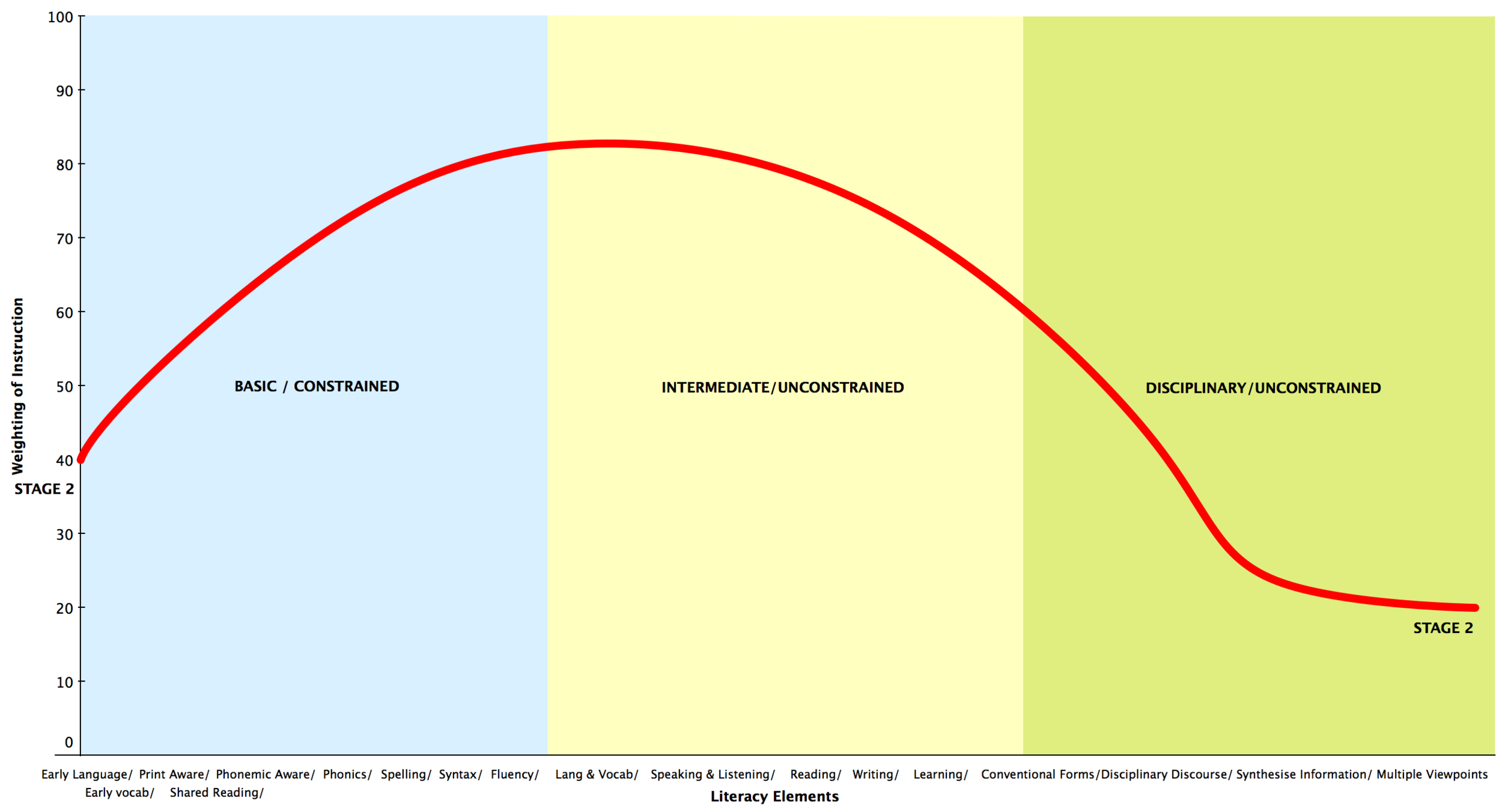

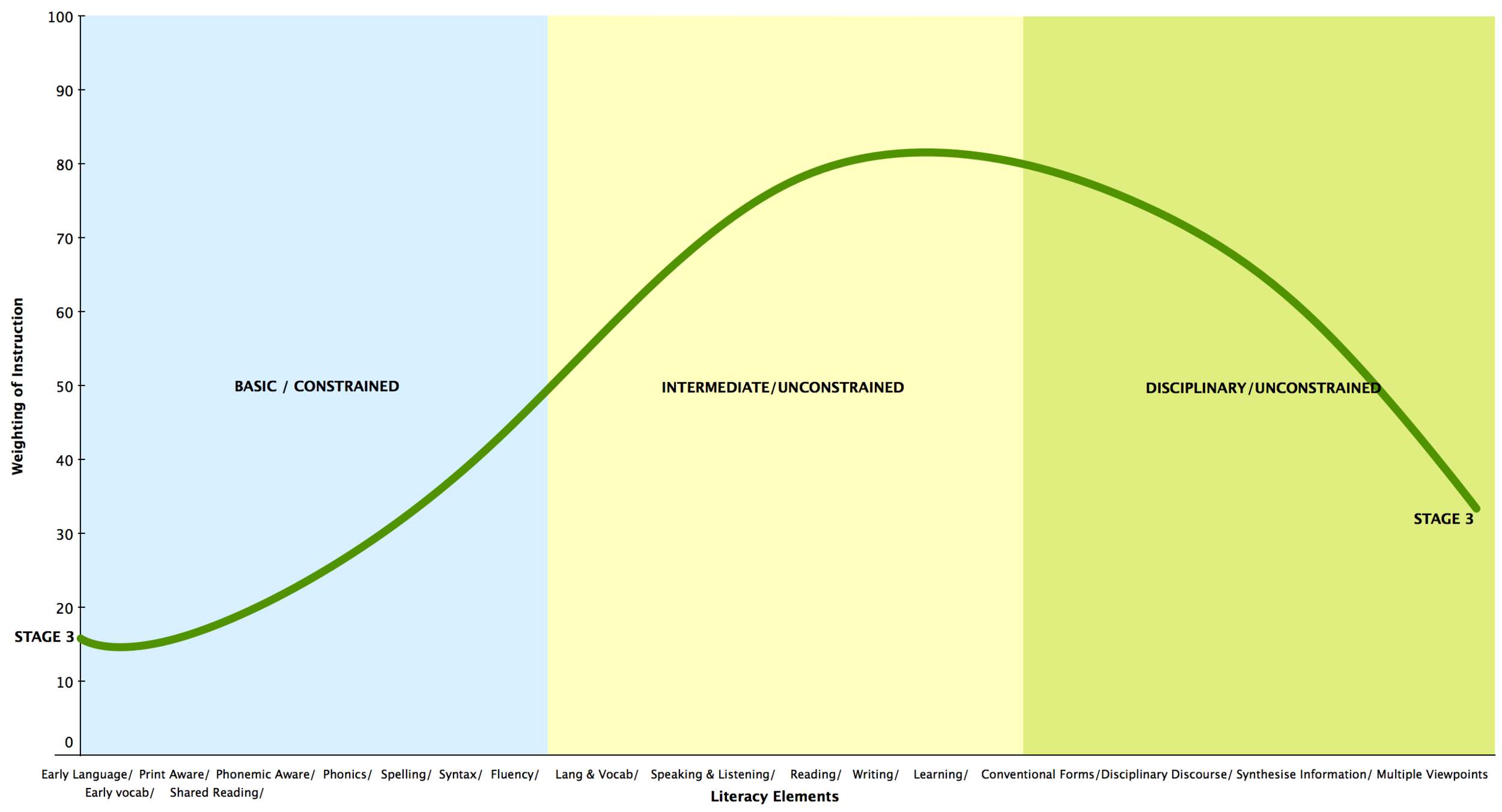

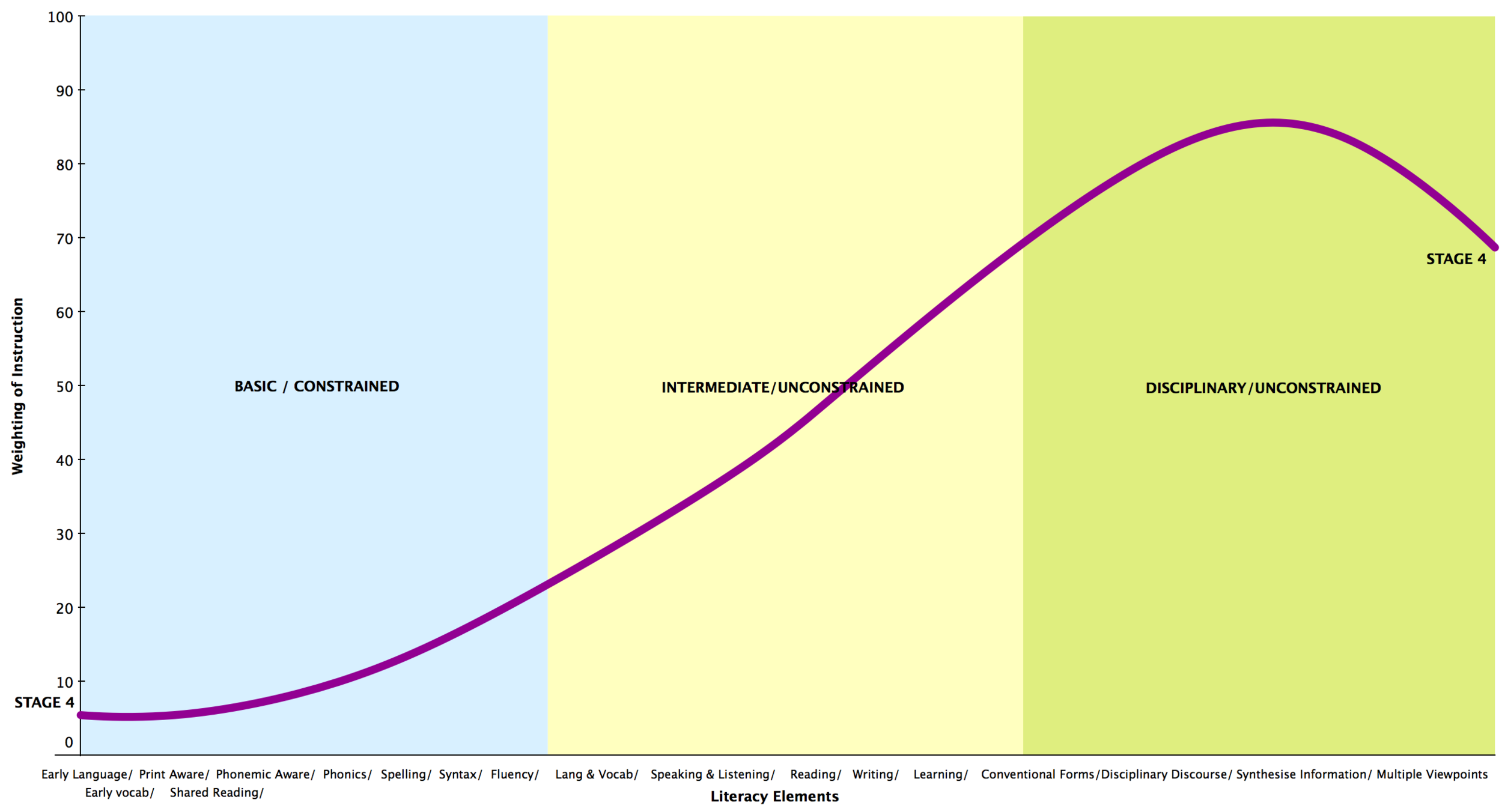

Therefore, a FOCUS ON LEARNING involves the most deliberate activities, since we know that any learning is only fragile unless reinforced and integrated into further stages of learning. The child (or emerging learner) is not faced with the prospect of developing such complex skills from the get go. There is a progressive, temporal dimension to this learning where the child is supported by others to develop foundational skills which lead into competency which lead to mastery which lead to further disciplinary practice. Meanwhile, the learner is surrounded by others (family, a community, peers, a culture) who exerts their own practices, knowledge, values and ways of navigating the spoken and written word.

What I do encourage is diligence and vision, empathy and expertise, instruction and reflection because "the child's understanding is not achieved in an instance or a flash, but requires multifarious repetition in multifarious context." (Moyal-Sharrock, 2010, pg 6). Learning also requires closure (or reinforcements). "Wittgenstein means to call to mind ... the intimacy with which seeing [and learning] is bound up with our embodiment, expectations, natural reactions, forms of life, and facts about our natural and social worlds.” (Affeldt, 2010, p. 276)

The teacher must be able to recognise this and take into account a range of factors when assessing the suitability of the goals for instruction, of the instructional materials, of the instructional methods, of classroom/instructional management, of community and parental engagement, of the role of home language and multilingualism, and of the forms of the assessment to be used (Au, 1998). A teacher's expertise should be both technical and socio-cultural. As Macedo (2001) suggests, “reading specialists ... who have made technical advancement in the field of reading ... [must] make linkages between their self-contained technical reading methods and the social and political realities that generate unacceptably high failure reading rates among certain groups of students.” (pg xiii)

References

Affeldt, S. G. (2010). On the difficulty of seeing aspects and the “therapeutic” reading of Wittgenstein. In W. Day & V. J. Krebs (Eds.), Seeing Wittgenstein anew (pp. 268 – 288). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Au, K. (1998). Social constructivism and the school literacy learning of students of diverse backgrounds. Journal of Literacy Research, 30(2), 297–319. doi:10.1080/10862969809548000

Macedo, D. (2001). Foreword. In P. Freire (Ed.), Pedagogy of freedom: ethics, democracy and civic courage (pp. xi – xxxii). Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Moyal-Sharrock, D. (2010). Coming to Language: Wittgenstein’s Social “Theory” of Language Acquisition. In SOL Conference 6-8 May 2010. Bucharest.

Wolf, M. (2008). Proust and the squid: the story and science of the reading brain. Cambridge: Icon Books.